Foraging for food

Foraging for wild food is a skill. A skill acquired with time and experience (usually someone else’s initially). Sometimes, these types of skills can be the hardest to learn from scratch - they can appear overwhelming and out of reach- especially if you do not have someone at hand to pass on their foraging knowledge. There is no way to instantly acquire the information you need - no book that is going to give you the confidence required to walk out the door and start eating a plant you have always considered a weed, let alone incorporate it into a daily meal in a way that you do not consider the flavour of your food a compromise for eating from the wild.

So what do you need to become a competent forager? At a minimum, you need a full cycle of seasons to understand how the plants change in growth, appearance, and flavour. Even then, wild food sources will change year to year depending on the growing conditions. So, to become a forager, an investment is required - time; a commitment to observing the seasons; and ultimately a little bit of patience. For our fast paced world, learning how to forage may perhaps be an ultimate example of delayed gratification.

Of course, foraging for food is the longest of food traditions, and in some parts of the world remains common practice. However, for those who have grown up in cultures where this skill has either not been a large component of modern food practice, or has been lost, there is some serious skill building required to become a competent harvester of wild food.

Where to start? By applying a few basic techniques to how you learn to forage for food, you can balance immediate reward from identifying an edible plant, with the delayed gratification that you receive when you make this investment and become a skilled forager. There will be a moment when you start a forage thinking “the purslane should be sprouting after that rain in the back paddock” that will be met with excitement, sense of accomplishment, and for me a profound sense of gratitude, when you find the fresh sprouts. I promise all your time spent observing the seasons will be worth it in this moment.

There are so many good reasons to learn how to forage for food. It is very sustainable - no monoculture, no pesticides, no water requirements beyond rainfall. It is free. It offers an opportunity to introduce a much broader range of food into our diets. It is also fun and incredibly rewarding to go for a walk and return with a meal. It beats a trip to the supermarket any day.

Steps to becoming a skilled forager;

Start in your immediate surrounds - your backyard, sidewalks, local beach or back paddock. In fact, once you have finished reading this, go for a walk and observe what plants you have growing. Don’t eat them yet.

Pick 5 easily identifiable, common (to your area) edible weeds or native plants to learn about - become knowledgeable in these first as opposed to knowing a little about a lot. It is safer as you will be confident in identification, and you will get more use from your harvest if you invest time into each of their flavour profiles and how they fit into your diet. Ask;

When and where do they grow? Keep a local map of where you find them and at what time of year.

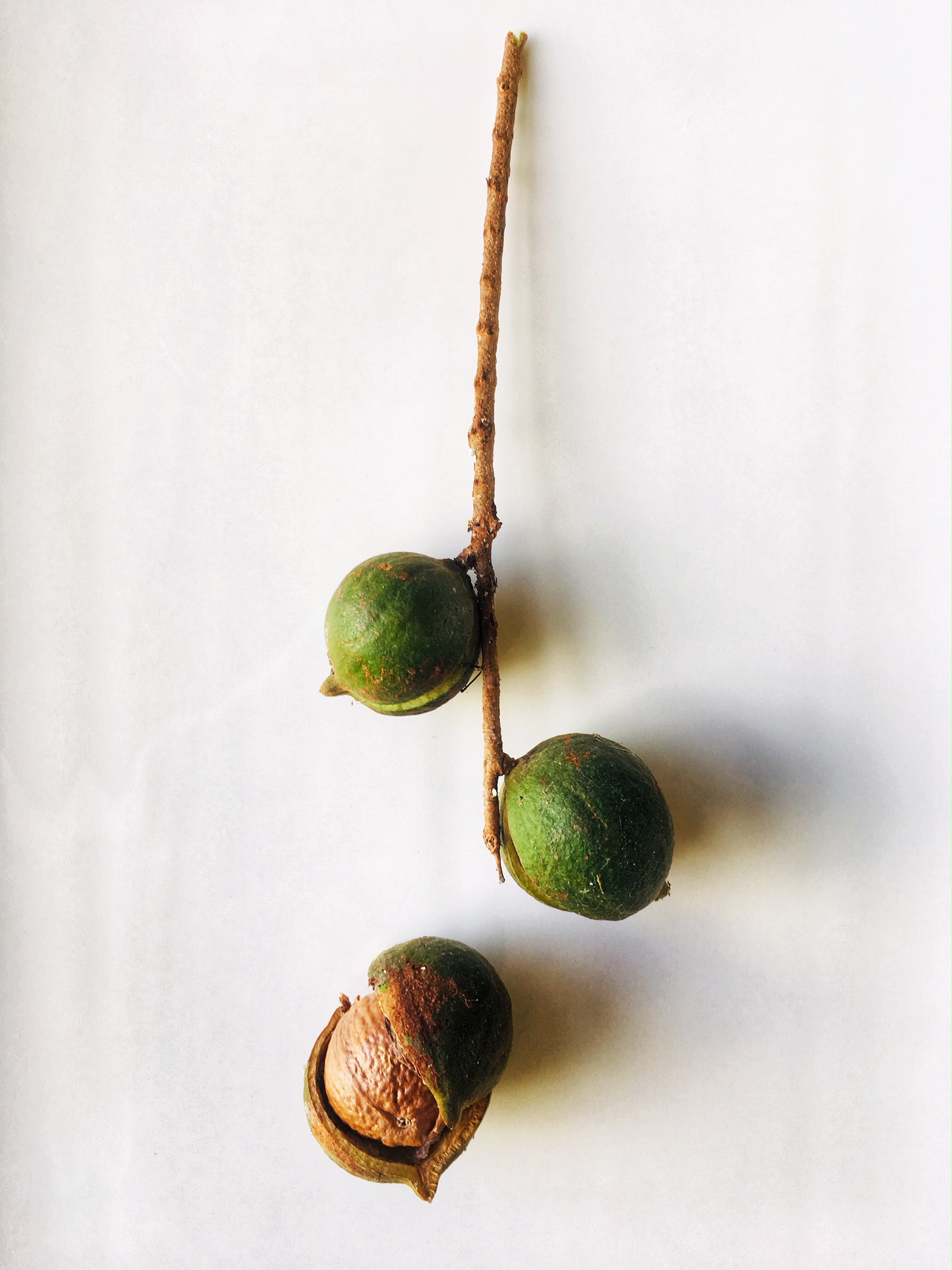

What do they look like in various stages of growth? Take photos. John Kallas, in ‘Edible Wild Plants’ refers to this (life cycle), as well as the growing conditions that affect the plant growth (life history), as the plants ‘life story’. He warns “Heed these life stories, and you will reap the great rewards that wild foods have to offer. Ignore them, and both your understanding and your success will be limited.” I completely agree.

What parts of the plant are edible?

When do the different parts of the plant taste the best? You will need to sample them at various stages of growth to know when best to harvest. Most plants are best to eat when young, early in their growth season, becoming bitter as they flower or age, however there are some exceptions to this. Keep notes.

How can I use them? Again I reference John Kallas who encourages you to look “…for the plant’s uniqueness, character, and potential” when tasting, as opposed to trying to make it fit an expected taste profile or compare it to tastes you are already familiar with. What other flavours would complement it? See my wild food recipes for some inspiration - but be bold and try your own experiments too.

Make time. Set an hour or two a week to go for a walk to practice identification and get a feel for the plants life cycle. Sometimes I just like to sit and look around me and try to count how many things I can see that are edible.

Once you can identify these 5 in all stages, and have use for each in day to day meals, pick another 5. Pretty soon you will realise you have acquired a new skill and rather than searching for a particular plant, you can start to harvest opportunistically.

The five edible weeds, (and an example of my notes for Northern NSW, Australia), that I started with were;

Purslane - my favourite edible weed.

Sprouts - March 2019 after the rain.

Location - under the grevillias, in the bare earth in middle paddock

Tastes best - early, before it sets flowers.

Taste profile when young - crunchy texture, lemony.

Can eat - leaves and young stalks

Harvest - cut young stems with leaves. Lasts well without wilt.

Uses - top couple of inches/leaves excellent raw in salads. Complimented by a zesty dressing, soft cheese, and sweet edible flowers. Can be pickled.

Dandelion

Farmer’s friend

Sow thistle

Curly dock

You can check this distribution map if you are in Australia to pick five edible weeds that grow in your region. You can also use the Wild Food Map app to see what others have found close by and add your find to the map. For my notes on Native Australian edible plants, see The Edible Garden.

There are, of course, some basic rules that should be followed. Some people don’t like rules. I get that. Sometimes there are so many rules you just feel like not following them once in awhile. When it comes to eating wild food however, I am a strong believer that rules exist for a reason - whether these are for safety or for ethical reasons. So the rules that I don’t think should be broken for any reason are;

Never eat a plant you can not confidently identify (or feed it to anyone). Better to take a photo and do some research than risk poisoning and being that person-who-taste-tested-a-wild-plant-they-couldn’t-identify in the emergency department…

Next rule is to be responsible in your harvest - some plants (such as Davidson Plums in Australia) have restrictions on wild harvesting without a permit. Be respectful of the land you are harvesting from, and never harvest all of the plant (unless it is a problematic weed for other reasons and by doing so you are being helpful).

What resources should I use?

There is clearly a current trend in foraging. Which I personally think is an excellent modern cultural shift in how we think about our food sources. This has led to an abundance of resources - a good thing. But not helpful if you are in your procrastinating “I haven’t started because there are so many things to read I don’t know where to start” phase. I am a perfectionist. I understand. The best advice I can give you is - don’t get overwhelmed. Pick a guide you can carry with you, or a web page you can access on your foraging walks, pick your 5 plants, and walk out the door (wear some good shoes, take a hat, some gloves, and a basket for your harvest. A spray bottle of water doesn’t go astray either to keep your greens fresh).

As a single helpful guide, I would recommend “Edible Wild Plants”. For details, as well as other recommended resources, see my foraging resource page.